“They complained to the city, and the city came down,” the owner of the Portland, Oregon, restaurant said. “They say ‘odor,’ but it’s just food, grilling meat.”

Pho Gabo in Portland, Ore.Courtesy Eddie Dong

March 20, 2024, 8:00 PM GMT+7

A pho restaurant in Portland, Oregon, has shuttered due to anonymous odor complaints, sparking a firestorm of backlash against the city’s smell codes, which residents and lawmakers slammed as potentially discriminatory.

After repeated anonymous odor complaints filed to the city and the threat of a hefty fine, Pho Gabo’s northeast Portland location closed its doors to customers Feb. 3. Once city officials learned about the issue in early March, they halted all subsequent investigations of odor code violations related to food establishments in order to re-examine the policy.

Pho Gabo owner Eddie Dong told NBC News that he first received notice that a neighbor had complained of the restaurant’s “cooking odors” in September 2022. The complaint caught him off guard; by then, Dong had been serving Vietnamese food at the restaurant for more than five years without incident. The sole complainer, a neighbor who lived several houses down from the restaurant, has not been identified.

“They complained to the city, and the city came down,” Dong said. “They say ‘odor,’ but it’s just food, grilling meat.”

The restaurant is one of three Pho Gabo locations Dong owns, but it is the only one in a mixed-use residential area of the city.

Portland’s odor code dictates that within certain zones, “continuous, frequent, or repetitive odors may not be produced. The odor threshold is the point at which an odor may just be detected.” In other words, an inspector evaluates it based on their own sense of smell.

Multiple inspectors have visited the restaurant in at least 10 different site visits over two years, according to public records released to NBC News by the Portland Bureau of Development Services. “The odors detected smell like a wok dish,” one inspector wrote in October 2023.

Dong tried a number of fixes, including deep cleaning the kitchen hoods and exhaust system, installing charcoal filters, and even cooking meat at his other locations and driving it to the Northeast Portland restaurant, according to the city’s records. However, the odor complaints continued.

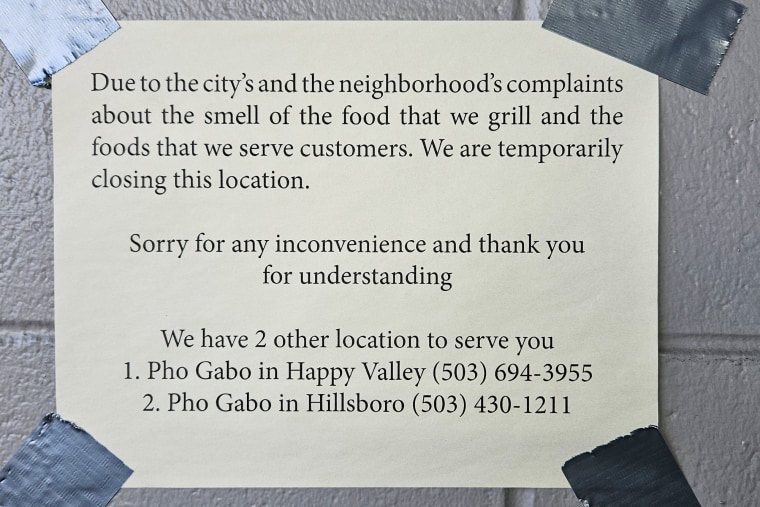

After the last inspection, Dong said that the city ordered him to either close the restaurant or pay a $4,000 fine. He added that if he did not close the restaurant, he would face an additional $3,600 fine. Dong closed his restuarant’s doors Feb. 3, posting a sign outside the door informing customers of the situation.

Dong said that now that one of his restaurant locations has closed, he is losing out on around $60,000 to $70,000 of revenue per month and struggling to pay his bills. The lease he signed to rent the building is not up until January, but he is unsure when he can reopen his business — if at all.

“I emailed the city and asked them what the next steps are. ‘Can I open without getting fined or put in a filtration system?’” he said. “I have no info on that, so the restaurant is just shuttered right now. It just sits there closed.”

On March 6, Portland Commissioner Carmen Rubio wrote on X that she was alarmed to learn about Pho Gabo’s closure. Rubio wrote that she ordered the city’s Bureau of Development Services to pause investigations into the odor code violations pending a re-evaluation by the city government.

A potentially discriminatory code

The motivations of the complaining neighbor — who is simply referred to as “COM” in official documents — is a source of tension, with some Asian American lawmakers raising questions about whether this is a discriminatory incident. They also questioned whether the odor code could be used to unfairly target certain businesses.

Oregon state Rep. Daniel Nguyen said he grew up just half an hour outside of Portland and was shocked to learn about Phở Gabo’s closure. “I was in disbelief, quite frankly,” Nguyen said. “Surely, it can’t be just one person, just one complaint that shuts down a business.”

Nguyen, along with four other Vietnamese state representatives, co-authored a statement released March 6 and shared with NBC News that slammed the odor code as a “dangerous precedent.”

The lawmakers — Nguyen and Reps. Hoa Nguyen, Hai Pham, Khanh Pham and Thuy Tran — who are all Democrats, wrote that the code, as it stands, is discriminatory and unfair, particularly to more vulnerable communities.

“We believe that, as currently written and enforced, the city’s odor code is discriminatory and not objective by any known standards, leaving out certain, minority-owned small businesses,” the lawmakers wrote.

“Policies may start with good intent, but they may have some of these unintended consequences,” Nguyen said. “They also could come from a place of implicit bias and trying to — not overtly — but indirectly trying to limit certain communities from doing business activity in certain areas.”

He also pointed out that Pho Gabo’s plight may have only gotten the attention it did due to the work of the Vietnamese community and the state representatives who rallied behind Dong.

“I almost feel like if we didn’t have a representation in government, in the part of the policymaking bodies, that sometimes these may not rise to the attention that we’ve gotten,” Nguyen said. “If there’s issues in our community, we need to be able to talk about them.”

![Anne Hathaway’s Celebrity Shoe Style [PHOTOS]](https://singexpress.news/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/7316aba8adf0fa7f551350cdb6d52baa-360x180.jpg)