In his new book, architect Vishaan Chakrabarti makes a case for building bigger to create more social cohesion and joyful communities.

By Mimi Kirk

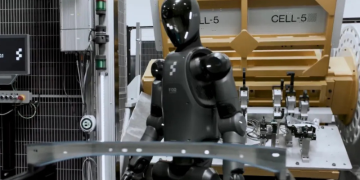

Designed by Vishaan Chakrabarti’s firm PAU, the Refinery at Domino in Brooklyn reflects the architect’s desire to create spaces that attract socioeconomically diverse crowds.

Photographer: Max Touhey/PAU

Ten years ago, the New York City-based architect Vishaan Chakrabarti made a pitch for transit-oriented density in a car-soaked nation. His book A Country of Cities: A Manifesto for an Urban America, extolled the benefits of “hyperdensity” — urban agglomerations with populations big enough to support mass transit, as embodied by high-rise-filled Asian cities like Tokyo and Singapore. Only by enacting policies that encouraged building up rather than sprawling out could cities conquer the inequality and housing crises that were roiling urban America.

“It wasn’t a unique argument,” he says, “but cities at that point were not getting the attention they are today.”

Chakrabarti, who helms the firm Practice for Architecture and Urbanism (PAU) and is known for work like a revived industrial complex along Brooklyn’s East River and a proposed reimagining of New York City’s Penn Station, now has a new manifesto — and it’s more ambitious. In The Architecture of Urbanity: Designing for Nature, Culture, and Joy, he argues that architecture and urban design are fundamental to addressing the biggest problems we face in society today: climate change and social division.

In the aftermath of the isolating Covid-19 pandemic and amidst the socioeconomic segregation the US continues to confront, Chakrabarti makes a case for more social friction in our built environment, where people from various backgrounds continuously come together eye-to-eye.

Such density, he argues, not only works to offset the effects of climate change through the reduced use of the automobile but ensures that we create a less fractious society. This “connective design” also works at the small-town scale, he says, and can help rural and urban areas achieve “rurbanity” — a state of mutual dependence and respect.

Chakrabarti recently talked to Bloomberg CityLab about how to create connective spaces, what’s missing from the European cities that urbanists love, and why automobiles are such divisive elements in the city. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How did your current argument emerge from your first book?

I found that people could get behind the idea that denser circumstances, in villages or cities, make sense in terms of the environment and the economy, but what they would come back to me with was, “Most of what we build is junk.” Transit-oriented development is soul crushing; it’s blue glass skyscrapers and Starbucks on the bottom level. I realized I needed to talk about architecture more and respond to the fact that our cities need to grow but that the design of them, which is often talked about in subjective and aesthetic terms, is frequently trivialized by political leaders.

How does the idea of connective design play a role?

We need to not just argue about our differences — we need to design for our unity. Designing for unity doesn’t mean that everyone becomes the same, as social friction is present. If you’re in a park or playground or building lobby where people of all stripes feel welcome, you for instance see a woman in an abaya and you realize that that person is just another human being. They’re not frightening. Social media has this way of pulling us into our silos and making us afraid of one another. The antidote is physical space; when it’s well designed, it keeps us eyeball-to-eyeball and we share joys and struggles as human beings.

Cars are problematic when it comes to connective design. It doesn’t matter if they’re electric because the problem with a car is it’s a divider. It’s a metal bubble and it keeps you from interacting with your neighbors. So the virtues of mass transit, public parks and well-designed buildings in cities are not just that they are good for the climate. They are also good for this sense of social coherence. If we’re going to live up to our promise as a country — a multicultural democracy — we need to have spaces that both reflect and perpetuate that.

A typical example of postwar American land use: a highway cloverleaf adjoining a surface parking lot in 1959 New York.Photographer: R. Krubner/ClassicStock/Getty Images

You write about how previous planning and design created suburban sprawl and segregation, and advanced the opposite of what you’re calling for.

We clearly designed an environment coming out of World War II that was segregationist and very carbon intensive. We literally said that we’re going to build highways and suburbs where Black people can’t get homes. It wasn’t called a design agenda but there was a tacit design to it all. Highways, suburbanization and white flight left Black and brown communities holding the pieces. Crime rose because of disinvestment, but a lot of those folks held on and kept those neighborhoods afloat through the struggles of the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s.

And then Seinfeld and Friends go on the air and the next thing you know college grads want to live in cities again and they start coming in, and so do the condo and real estate developers. So the people who stayed with their neighborhoods through the really hard times are getting forced out. Part of what is so important about knowing that history is seeing that if the country can be designed one way, we can do something else — all in a few decades.

How do you create a space with social friction? What examples already exist?

The idea that you can create a place for all races and classes sounds very utopian, and it is very hard in the economic structures we live in to make things more mixed. But these places do exist or they exist in enough measure. One of the projects I’ve worked on, Brooklyn’s Domino Sugar Refinery, which was renovated into office space, residences and parkland, is quite socioeconomically diverse. But many of the places we have tried to build for everyone have unfortunately become quite homogeneous.

For years, Copenhagen, for example, was touted as a paradise for urban planners. And it’s a lovely city. But when you ask where the immigrants are, the response is, “Oh, they’re over there,” meaning not in the center of things. I was involved in the High Line in Manhattan, and we wanted it to be a very welcoming place. But people in the projects around it told us that they didn’t feel welcome in it — that it was too sparkly.

So a lesson when designing is that people from all walks of life should feel comfortable in the space, and it’s important to have that intentionality. And this is in fact good from both an environmental and socioeconomic standpoint. You don’t have to always use the sexiest new material, the shiniest new systems. It’s about amplifying what’s there and celebrating it.

You call the type of housing that can provide density and social friction “Goldilocks housing,” as it’s three stories — not too large and not too small.

You take rowhouse height and expand the width and get the basic building block of some of the cities we love the most. In the US that’s a lot of Boston, DC and Philadelphia. To expand it you put 12 or 15 flats connected to a cage elevator in the middle. You can house a lot of people this way, and people feel connected to trees and nature but it’s dense enough to support mass transit. In these kinds of apartments there’s a sense of social glue with your neighbors. If there’s an elderly neighbor who hasn’t been seen in a couple of days, concern grows. It’s an urban form of living but it’s not skyscrapers.

Get the Morning & Evening Briefing Asia newsletters.

Start every morning with what you need to know followed by context and analysis on news of the day each evening. Plus, the Weekend Edition.

Bloomberg may send me offers and promotions.

Sign Up

By submitting my information, I agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

In the US today, people think of Manhattan when they hear the word “urban,” but there are a lot of urban places in this country outside of the major cities. A lot of younger families who can’t afford Manhattan, DC or San Francisco are living in places like San Antonio or Nashville, and they want an urban lifestyle that’s not car-dependent, where you can drop a kid off at school without getting in a car. That’s the litmus test.

You argue that resources must be put toward these types of spaces. What impedes this and how can that be overcome?

We are a very wealthy country, and our policy questions are so oriented toward spending billions of dollars on huge new projects. But a lot of the housing stock in the US needs reinvestment rather than razing and rebuilding.

For instance, I notice how pockmarked a lot of the cities of the Great Lakes are with vacant lots and dilapidated housing. We can build infill housing while homeowners receive resources to fix up the dilapidated houses. With issues of gentrification, the people who get hurt the most are renters. If you own your home, you get to participate in your neighborhood improving. We should be rethinking the mortgage interest deduction so that we redirect those funds for anything over the median price of a house to a renters’ deduction, so that renters can buy and build equity in their neighborhoods.

Once you’ve done this politically, the communities need to be built. Vice President [Kamala] Harris is talking about building 3 million new homes, and many of the more progressive parts of the Democratic Party are talking about the housing crisis. This is a harbinger of where things are going. It’s not just about political change, but physical change.

![Anne Hathaway’s Celebrity Shoe Style [PHOTOS]](https://singexpress.news/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/7316aba8adf0fa7f551350cdb6d52baa-360x180.jpg)