The first museum survey of modernist architect Paul Rudolph dwells in the margins of his polarizing works, many of which now exist only on paper.

Nothing remains of the cabanas that Paul Rudolph designed for the Sanderling Beach Club in Sarasota, Florida. A series of white, low-slung structures with vaulted ceilings that the architect designed early in his career in 1952, the huts were wiped out after Hurricane Helene reached Central Florida on Sept. 26.

While the destruction of the modernist beach club is only a footnote in the devastation caused by the storm, it’s a loss for the postwar school of architecture known as Sarasota Modern. It’s also a loss for fans of Rudolph, a modernist architect who reached the height of his profession in the 1960s but found his influence and reputation fade before the end of the decade.

Many of Rudolph’s finest works belong to such footnotes: structures that were demolished, renovated beyond recognition or never realized in the first place. The architect, who died in 1997, took on the conventions of modernist design, rebelling against what he described as the “goldfish bowls” of glass skyscrapers and urging a return to the primal texture of “caves.” Rudolph won fame with his sweeping plans for Brutalist megastructures that sometimes operated on the scale of cities, but when tastes changed the public lost interest just as quickly. With many of his ideas abandoned to neglect or confined to filing cabinets, Rudolph’s drawings represent the best measure of his work.

That’s one message in a new survey of Rudolph’s work on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. “Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph” touches on all the significant periods of the designer’s output, from his early projects in Florida to his radical tenure at Yale to his retreat to projects in Asia. With another one of Rudolph’s buildings gone, the case for reframing his work seems that much stronger. Rudolph has never been the subject of a standalone museum show, according to curator Abraham Thomas, and the Met hasn’t put on a modern architecture survey in 50 years.

Yet the show never quite makes an argument for what the audience needs to know about Rudolph now, or why his admirers have so passionately fought for his buildings even as their owners call for the wrecking ball. “Materialized Space” considers Rudolph’s work as texts, asking viewers to indulge in the marginalia, but the Met’s modest presentation fails to summon the drama of the work that it cites.

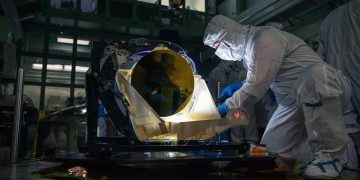

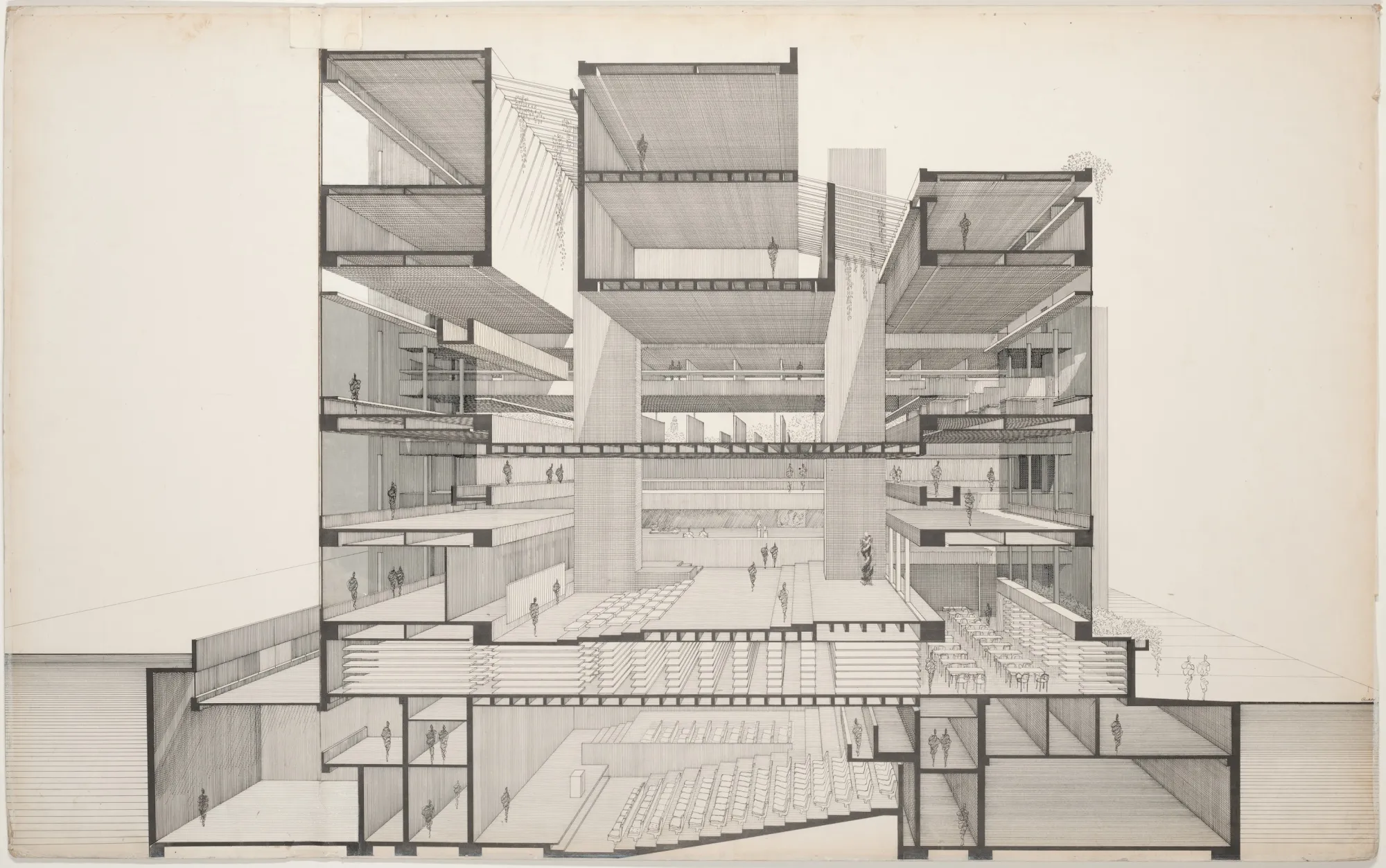

First and foremost, it’s a drawing show. The exhibit firmly identifies Rudolph as a draftsman, and moreover a designer whose decisions about massing and materials flowed from the page. There’s a display of his pens and pencils along with his triangles, templates and other drawing tools: standard fare for this kind of monograph. Instead the show’s structure sets it apart. It moves in reverse chronological order, beginning with late 1980s drawings and models for unbuilt towers in Hong Kong, Jakarta and Singapore and proceeding (loosely) toward late 1940s designs for built and unbuilt homes around Sarasota Bay.

In this presentation, the Yale Art and Architecture Building — a 1963 Brutalist building that stands as one of his best-known works — isn’t the fulcrum of a career framed on one side by ferocious ambition and on the other by whispers of failure, but rather another point in an unbroken line of concepts driven by graphite pencil.

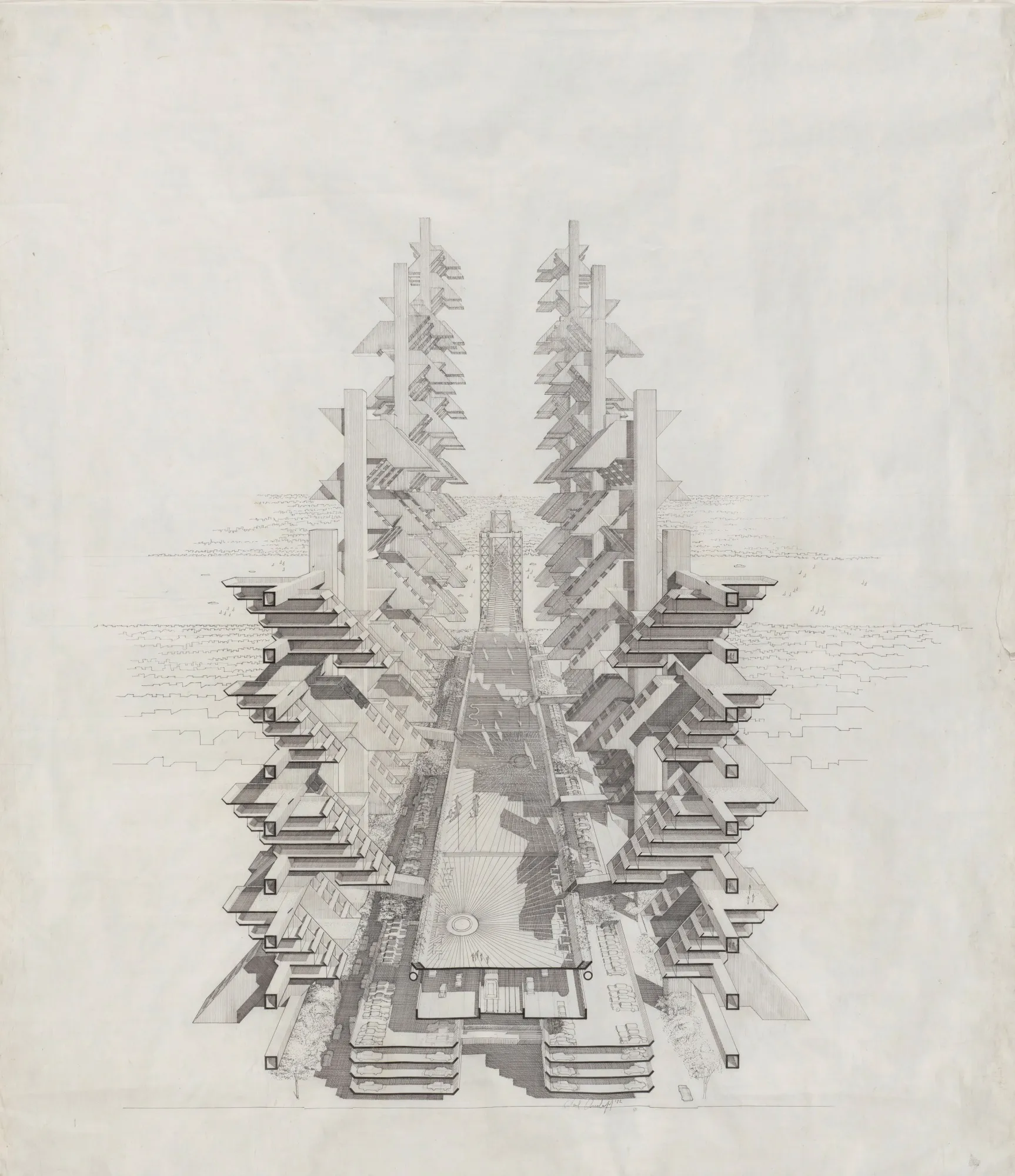

And no wonder, really, why the Met would take this approach. Rudolph’s drawings just work: They showcase both the scale of his thinking and the reach of his experiments. One 1966–68 drawing shows Rudolph’s proposal for a public housing complex in Fort Lincoln, then a greenfield site in northeast Washington, DC, that was being developed as a Great Society project after the riots. The architect’s isometric drawing reveals row upon row of housing modules piled up like shipping containers: simple and elegant in its geometry, but typical of the arrogance of housing experiments during the urban renewal era. A ground-level perspective drawing of the same complex, however, shows cantilevers that form terraces, skybridges that connect buildings and stairwells that might have been stoops. Rudolph’s “New Town” proposal was never built, but the drawings make it clear that his conviction to design homes — not just housing units — was sincere.

Rudolph’s drawings make even his most hostile ventures seem like arguments worth hearing out. “Materialized Space” includes several artifacts related to one particularly maniacal scheme known as the City Corridor. More of a provocation than a plan, this urban terraforming proposal was the Ford Foundation’s answer to Robert Moses’ push for a Lower Manhattan Expressway. Where Moses wanted to pave paradise for an urban highway, Rudolph would have erected a mountain range instead: a two-mile-long building, fully concealing a freeway below ground and a bottle society above.

Rudolph’s ideas for a line city would make the Saudi funders of Neom blush. Still, for a conceit that another designer might have treated as a folly, Rudolph embraced the proposal as a platform detailing his vision for modular construction, urban transit and public space. And of course, sculptural form.

Archival materials help to give a sense for how these ideas landed with the public. Heaping examples of news articles and magazine covers convey how Rudolph climbed to the top — however briefly — although these documents compete with the drawings for the viewer’s attention. There are almost no photos on view, which makes a tweedy kind of sense: Photographs aren’t primary texts, images bring their own judgments to bear, and so on. But the catalog that accompanies the show reveals a missed opportunity for the exhibit. An interior photo of Rudolph’s (since demolished) Burroughs-Wellcome Company Headquarters in North Carolina, paired with a 1970–72 perspective drawing of the space, testifies to the integrity of the architect’s process, for a building that was bulldozed in 2021.

The Met might have found a smaller gallery for “Materialized Space” — but it would have been a broom closet. The compact presentation tends to flatten drawings of Manhattan megalopolises and Florida bungalows as same-same. More room might have helped the curator, Thomas, achieve some of the things he is trying to do to reach new audiences. There’s a video, for example, that includes clips from popular movies and shows with locations designed or inspired by Rudolph, including The Royal Tenenbaums (which features a scene shot at his townhouse 23 Beekman Place) and Loki (whose production design and set for the Time Variance Authority borrows liberally from UMass Dartmouth). Put it behind a curtain with a bench — instead of in the center of the gallery — and Brutalist-curious visitors might be able to watch it.

While there are some popular handholds in “Materialized Space,” including the video and a collection of objects collected by Rudolph, Thomas is laser-focused on a narrow (and intriguing) theory about the architect’s process. Rudolph was one of just a few “name on the door” architects of the era who had a hand in every production drawing, the curator writes in a catalog essay. Thomas finds a direct correlation between Rudolph’s drawings and choice of building materials, noting that his interest in highly textured materials flowed from his drawings of light and shadow, not the other way around. “These perspective views, elevations, and sections often acted as more effective advocates for his architectural vision than the finished buildings,” Thomas writes.

Which is not to say that “Materialized Space” is an exhibit for insiders, exactly. Rudolph’s life outside of the drafting table goes largely unexplored. “Materialized Space” offers a thorough presentation on Rudolph’s immersive interiors, which critics tied to his sexuality, at times dismissively. Rudolph was gay and remained closeted his whole life. Historian Timothy Rohan finds a positive narrative connection between Rudolph’s dazzlingly soft interiors and his fortress-like building schemes, while “Materialized Space” makes no mention of his sexuality, focusing squarely on the compositions.

Neither does “Materialized Space” dip into the hottest debates over the fate of the architect’s most controversial built projects. Threats to Rudolph’s Orange County Government Center building in Goshen, New York, captured headlines for the better part of a decade before it was partially demolished in 2015. Today it stands as an architectural chimera, halfway preserved and entirely desecrated, the worst sort of compromise and a powerful cautionary tale. The project’s mentioned just once in the catalog.

Maybe it’s asking too much to expect the Met to recreate one of Rudolph’s criminally overlooked (and mostly disappeared) interior designs, or to suffuse the exhibit with the notorious paprika-colored carpet of the Yale architecture building that now bears his name. There are surely ways to bring a Gen Z audience into the Brutalist fold that are worth considering. Still, it’s not a huge ask that a show billed as a major survey should have a strong point of view about why the work matters now — and enough room to express it. To find it in this survey, viewers need to read between the lines.

![Anne Hathaway’s Celebrity Shoe Style [PHOTOS]](https://singexpress.news/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/7316aba8adf0fa7f551350cdb6d52baa-360x180.jpg)