New platforms for Sydney’s expanded city-center Metro line mark the latest step in the ongoing transformation of its central transit hub for trains and buses.

By Karen Leigh

(For more Bloomberg CityLab coverage of design, architecture and the people who make buildings happen, sign up for the Design Edition newsletter .)

Sydney’s most celebrated architectural landmarks stand tall over the harbor: the iconic sails flanking the Jørn Utzon-designed Opera House, the sweeping steel arch of the Harbour Bridge. The latest, however, is below the city’s streets.

A renovation of sprawling Central Station, the Australian city’s answer to Grand Central in New York and King’s Cross in London, was unveiled last year, a roughly A$1 billion ($672 million) overhaul led by Woods Bagot. Under one of the firm’s mantras of focusing on passenger experience, much of the station’s dark warren of tunnels and concrete gave way to airy concourses, vaulted ceilings and walls of engineered sandstone.

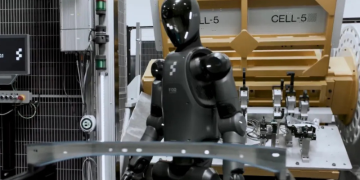

The latest section — a set of sleek platforms serving the main city center section of Sydney’s Metro rail, which began running earlier this week after some seven years of construction and more than A$20 billion in costs — is now open.

The revamp comes in time for Central to serve as a showcase for the line, whose driverless high-speed trains will run every 4 minutes at peak hours. Sydneysiders are hoping the much-anticipated expansion to Australia’s biggest public transport project will revolutionize how people get around a city where rail and bus service can be slow and prone to delays.

Metro is transforming how Sydney’s train stations are designed, too. That starts with Central, which wants to be a destination in itself for the thousands of people who pass through each day.

“Typically with infrastructure-led projects, getting an architectural lens on these things is sometimes not the highest priority,” John Prentice, a principal and global transport sector leader at Woods Bagot, said during a visit to the station. Here, a key component “was really around shifting Central to not be a place of ‘through,’ but ‘to.’”

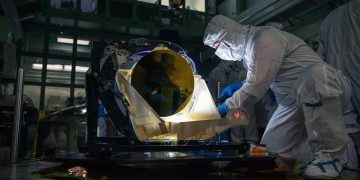

Riders reach the Metro platforms via a deep escalator descent ringed by towering walls of parallelogram-shaped blocks. These decorative features are made from molded glass-reinforced concrete that’s been designed to look like sandstone. The natural stone itself has for centuries helped define Sydney’s architecture and style. But an alternative to the resource was needed given the grand scale of what the station would be using.

In envisioning the concourses that criss-cross overhead — funneling commuters and tourists to the Metro, overground trains, and through to buses and surrounding office buildings — architects faced a delicate task of merging the old with the new. Some of Central Station’s original fixtures are more than a century old and include an iconic street-level sandstone clocktower, known in the pre-iPhone era as the “workers’ watch,” which needed to be preserved and blended with modern components.

Excavation led to discoveries that made architects adjust course, like brickwork on the site’s electric building that led them to skip the cladding they’d planned. Designs needed to be both visually effective and serve a function befitting a major train station, like giant louvered windows that are both nice to look at and keep air flowing.

Perhaps most challenging, the construction needed to happen while Central Station was still in daily use.

Natural light is now a hallmark of what was once a mostly dim station. The vaulted roof over one concourse is comprised of sections Prentice described as “hockey sticks” and dotted with skylights. Built in modules a couple hours up the coast in the city of Newcastle, then transported to Sydney and installed, the ceiling allows light to cascade in. Elsewhere in the remodel, light floods through elevator apertures and even more skylights, through which the shadows of people passing overhead are sometimes visible. Even at the below-ground concourse leading to the Metro platforms — which also features the station’s now-signature walls of engineered sandstone — the effect is that of being at street level.

The upgrade, delivered by construction firm Laing O’Rourke, was designed by Woods Bagot in collaboration with John McAslan + Partners. “Making the journey through is quite a nuanced thing for us,” Prentice said. “If we look at all the aspects of the movement and the experience of moving through the station, rather than just big moments of the entries or the lights.”

Public art, including an outdoor installation celebrating Australia’s Aboriginal heritage, now runs through the station. Acoustics lend a calming hush to the rumble of carriages, thousands of footsteps — and even to booming announcements for trains to the suburbs, or further, to cities like 2032 Olympics host Brisbane.

While passengers wait for Metro trains, they can walk a giant racetrack by Melbourne-based artist Rose Nolan embedded in the floor of the concourse and festooned with sayings fit for a commute: “Be aware of each mental note as it arises,” reads one.

Even as the Metro platforms usher in a new era of Sydney transport, Woods Bagot preserved a palimpsest of Central’s heritage in its concourses. Artifacts found in the excavation of the site — which was home to a vast cemetery in the 1800s — are now on display. Large touch-screen video installations give a history of the station. Some waiting benches are made of timber salvaged from its past. At one street entrance, the style of Central’s beloved black-and-white wood platform signage has been repurposed using contemporary materials.

“It’s about making that emotional connection to the place — that’s fundamental,” Prentice said. “That aspect of ‘when you arrive at Central Station, you know you’re at Central Station’ was so important for the design.”

![Anne Hathaway’s Celebrity Shoe Style [PHOTOS]](https://singexpress.news/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/7316aba8adf0fa7f551350cdb6d52baa-360x180.jpg)